The Cotton Gin Got Sleeker: How Technology Fuels Exploitation Then and Now

The Industrial Revolution didn’t just bring factories, machines, and faster production—it reshaped entire economies and re-entrenched systems of exploitation. In the early American republic, one of the clearest examples of this was the relationship between Northern industry and Southern slavery. Technological innovations like Eli Whitney’s cotton gin didn’t lessen the burden of labor—they made slavery even more profitable.

The Roots of the Cotton-Slave Economy

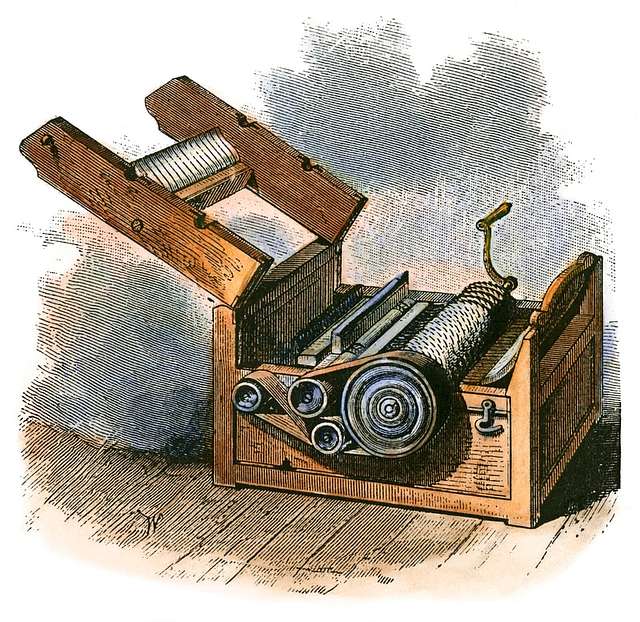

Before the cotton gin, growing and processing cotton was an incredibly labor-intensive task. Short-staple cotton, which grew well in the Deep South, had sticky seeds that were difficult to remove by hand. Planters often avoided it in favor of other crops. But in 1793, Eli Whitney’s cotton gin changed that. It could clean short-staple cotton quickly and efficiently, making large-scale cotton cultivation wildly profitable—as long as there was a captive labor force to plant, pick, and process it.

This is where slavery stepped in—and ramped up. Between 1790 and 1860, U.S. cotton production increased more than 100-fold. So did the number of enslaved people in the South. Cotton became the backbone of the Southern economy and the most important export of the United States. By 1860, the South was producing 75% of the world’s cotton.

The Northern Mills and the Global Demand

So where did all that cotton go? To the North—and across the Atlantic. Northern industrial cities like Lowell, Massachusetts, and later Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, became hubs for textile mills and manufacturing, producing cotton goods for both domestic and global markets. As the textile industry matured, it created downstream demand for more industrial growth—railroads, iron foundries, shipping, and eventually steel production.

The need for strong materials to build machines, looms, and transportation infrastructure led to the birth of steel mills. As cities industrialized, the appetite for cotton didn’t decrease—it expanded. Southern plantations supplied the raw materials; Northern factories processed them and turned a profit. Both economies—though seemingly different—were tightly bound by a single thread: enslaved labor.

Profiting from Enslavement, Nationally

It’s convenient to think of slavery as a Southern issue, but the economic benefits were national. Banks in New York and Boston financed plantations and insured enslaved people as property. Shipping companies moved cotton to mills. Wall Street’s early growth was fueled by these very transactions. Northern industrialists, investors, and everyday consumers were entangled in a system that relied on brutal labor in the South.

The cotton gin didn’t create this system, but it made it more efficient. It automated the easiest part—seed removal—and left the backbreaking work of planting, picking, and processing to human beings who were denied their humanity. In doing so, it linked Southern slavery and Northern industry in a feedback loop of profit and dehumanization.

The Modern Echo: Exploitation in the Gig and Global Economy

Fast forward to today, and you can see echoes of this dynamic in the global economy. Technological innovation is still marketed as a path to liberation—apps, automation, smart devices. But look closer. That “fast” delivery? That $5 T-shirt? They’re made possible by underpaid workers in warehouses, on bikes, in factories overseas. The labor didn’t disappear—it was just outsourced and hidden.

Gig economy platforms claim to “empower” workers with flexibility, but many ride the same razor-thin margins and lack of protections that industrial laborers faced in the 19th century. Just like the cotton gin increased productivity while deepening dependence on enslaved labor, today’s platforms increase convenience while entrenching a new kind of precarious work.

The Bottom Line

Technology is never neutral. It exists in context—and that context is shaped by who has power and who does the work. The cotton gin didn’t end labor; it shifted who benefited from it. The same goes for today’s tools. The sleek interface may have replaced the spinning jenny or steel loom, but the exploitation underneath remains deeply familiar.

The cotton gin just got sleeker.